Collective exhibition at David Krut Projects

David Krut Projects is pleased to present Reclaiming Quarters, a collective exhibition by Mary Sibande, Lusanda Ndita, Hoek Swaratlhe of work made in collaboration with printer Sbongiseni Khulu at the David Krut Workshop.

David Krut Projects is pleased to present Reclaiming Quarters, a collective exhibition by Mary Sibande, Lusanda Ndita, Hoek Swaratlhe of work made in collaboration with printer Sbongiseni Khulu at the David Krut Workshop.

The exhibition opens October, 19th 2024 at 11am at David Krut Projects, The Blue House, 151 Jan Smuts Ave. Parkwood.

In late 2023, the David Krut Workshop (DKW) was approached to collaborate as part of The Occupying the Gallery mentorship programme, established by Mary Sibande and Lawrence Lemaoana. The aim of the programme is to introduce a number of artists from different backgrounds to the world of art and the myriad of spaces/opportunities therein. As a collective the artists would “take up residence in and transform an otherwise used space into an active open working environment that offers access into artistic processes” to create works that are then showcased, moving through the different aspects of collaboration, printmaking and institutions as they go.

This exhibition delves into the notion of “quarters” as a potent symbol of spatial control and the dehumanizing conditions imposed on non-European people during South Africa’s apartheid era. The term “quarters” refers not only to the physical spaces—domestic worker quarters, migrant labour hostels, and segregated townships—but also to the broader structures that shaped the personal and collective identities of millions. Through each artist’s unique lens, the works presented transform these spaces of oppression into sites of memory, resistance, and possibility.

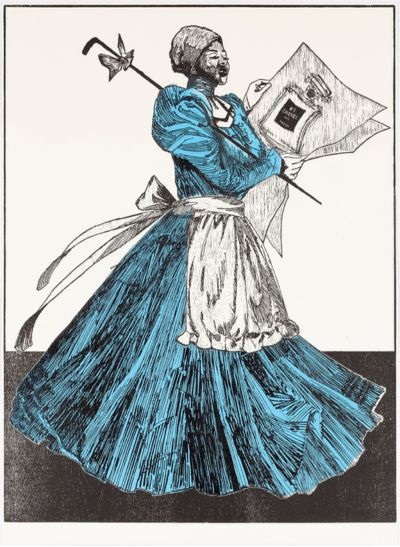

Domestic Workers’ Quarters

In Sibande’s work, the domestic workers’ quarters represent the invisible servitude imposed on Black women during apartheid, reflecting strict racial and class divides. These small, isolated spaces behind white employers’ homes symbolized a life of constant availability, where domestic workers’ existence was bound to their employers’ needs yet meant to remain unseen. Sibande reclaims these spaces, transforming them into symbols of endurance and dignity. Through her avatar Sophie, who embodies the experiences of her ancestors, Sibande challenges historical injustices. Sophie’s extravagant Victorian-style dress, adorned with tulle, ruffles, lace, and chiffon, redefines her identity beyond servitude, subverting the outdated notion that reduced Black women to mere household objects.

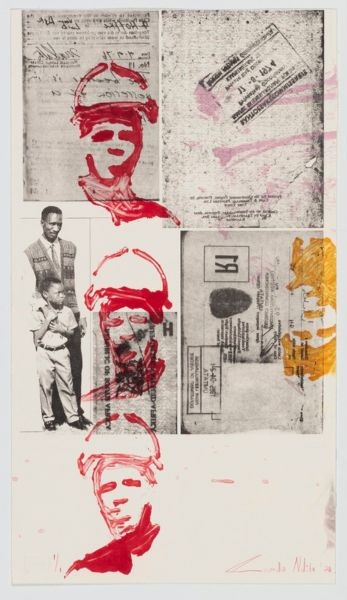

Men Leaving the Homelands for the City

Ndita’s exploration of migrant labour systems highlights the harsh realities faced by men forced to leave their rural homes for the city’s industrial workforce following the passage of the Glen Grey Act in 1894. These overcrowded hostels, designed to dehumanize, severely restricted personal freedoms, isolating men from their families and reducing them to mere labourers. The systemic fragmentation of families and poor living conditions reveal the brutal impact of colonialism, which introduced the segregation of native Africans, further disenfranchised them, and controlled their economic opportunities, laying the groundwork for apartheid’s migrant labour and Bantu Homeland systems. Ndita’s work evokes both the loss and resilience of these men, honouring their struggles while critiquing the ongoing legacies of displacement. Similarly, Ndita examines the nuclear family structure within society, masculinity, and historical connections. His visual representations explore the duality of presence and absence, depicting the role of male figures over three generations of his familys story. By incorporating historical artefacts, like his grandfather’s dompas and work permits, Ndita confronts viewers with South Africa’s harsh past and its lasting impact on communities, families, and individuals.

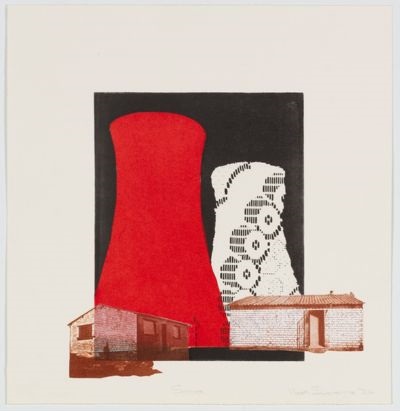

Non-European Houses

Non-European Houses

Swaratlhe’s work focuses on the aftermath of the Group Areas Act of 1951, which forcibly relocated non-European communities to segregated townships like Soweto. These hastily constructed, inadequate homes were designed to entrench racial divisions, ensuring that Black, Coloured, and Indian populations remained socio-economically disadvantaged. Swaratlhe reveals how these spaces, initially intended as sites of control, became hubs of community, resistance, and survival. By highlighting these “non-European quarters,” Swaratlhe encourages viewers to consider how marginalized communities transformed their imposed circumstances into powerful spaces of resilience and solidarity. Similarly, Swaratlhe examines the racial disparities in housing conditions for European and non-European South Africans in Soweto post-1951. Through a combination of architectural plans, photography, and found objects, Swaratlhe brings attention to the social inequalities experienced by indigenous individuals and the limitations imposed on their living spaces.

Together, the artists in this exhibition reclaim the notion of “quarters,” transforming them from sites of oppression into spaces of memory, defiance, and transformation. By revisiting these confined, controlled environments, they open possibilities for new narratives of healing and empowerment. These works challenge us to reflect on the physical and psychological spaces we occupy and the histories they hold.

Working with collaborative printer, Sbongiseni Khulu, Sibande, Swaratlhe and Ndita were collectively able to identify the various mediums needed to portray everyone’s artistic vision without impeding on their creative outlet. Their bodies of works gave way to exploration within the accustomed structural confines of lithography, monotype, relief, object printing and collage.